Subsection 6.5.1 Requirements of Fuel Injection System

The external fuel system stores and delivers clean fuel to the fuel injection system. In delivering. fuel to the cylinders, the fuel injection system must fulfill the following requirements:

- Meter or measure the correct quantity of fuel injected.

- Time the fuel injection

- Control the rate of fuel injection

- Atomize or break up the fuel into fine particles according to the type of combustion

- chamber

- Pressurize and distribute the fuel to be injected

The desired condition is to create a homogeneous mixture in the combustion space, in the correct proportions, of the smallest possible fuel particles and air. Although it is not possible to achieve an ideal condition, a good fuel injection system will come close.

Metering.

Accurate metering or measuring of the fuel means that, for the same fuel control setting, the same quantity of fuel must be delivered to each cylinder for each power stroke of the engine. Only with accurate metering can the engine operate at uniform speed with a uniform power output.

Timing.

In addition to measuring the amount of fuel injected, the system must properly time the injection to ensure efficient combustion so that maximum energy can be obtained from the fuel. When fuel is injected too early into the cylinder, it may cause the engine to detonate and lose power, and have low exhaust temperatures. If the fuel is injected late into the cylinder, it will cause the engine to have high exhaust temperatures, smoky exhaust, and a loss of power. In both situations, fuel economy will be low and fuel consumption will be high.

Controlling the Rate of Fuel Injection.

A fuel system must also control the rate of injection. The rate at which fuel is injected determines the rate of combustion. The rate of injection at the start should be low enough that excessive fuel does not accumulate in the cylinder during the initial ignition delay (before combustion begins). Injection should proceed at such a rate that the rise in combustion pressure is not excessive, yet the rate of injection must be such that fuel is introduced as rapidly as possible to obtain complete combustion.

An incorrect rate of injection will affect engine operation in the same way as improper timing. If the rate of injection is too high, the results will, be similar to those caused by an excessively early injection; if the rate is too low, the results will be similar to those caused by an excessively late injection.

Atomizing the Fuel.

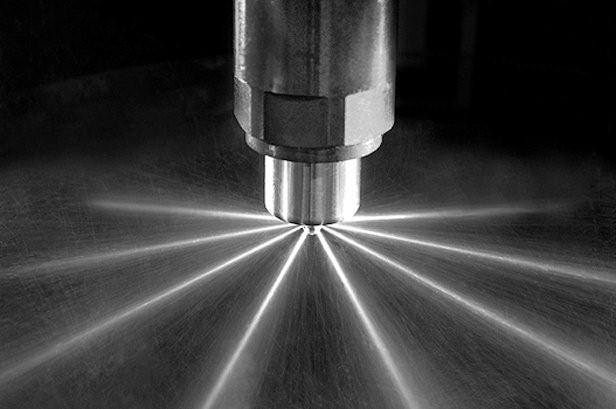

As used in connection with fuel injection, atomization means the breaking up of the fuel, as it enters the cylinder, into small particles which form a mist-like spray. Atomization of the fuel must meet the requirements of the type of combustion chamber in use. Some chambers require very fine atomization, others can function with coarser atomization. Proper atomization facilitates the starting of the burning process and ensures that each minute particle of fuel will be surrounded by particles of oxygen with which it can combine.

Atomization is generally obtained when the liquid fuel, under high pressure, passes through the small opening, or openings, in the injector or nozzle. The fuel enters the combustion space at high velocity because the pressure in the cylinder is lower than the fuel pressure. The friction, resulting from the fuel passing through the air at high velocity, causes the fuel to break up into small particles.

Pressurizing and Distribution of Fuel.

Before injection can be effective, the fuel pressure must be sufficiently higher than that of the combustion chamber to overcome the compression pressure. The high pressure also ensures penetration and distribution of the fuel in the combustion chamber. Proper dispersion is essential if the fuel is to mix thoroughly with the air and to burn efficiently. While pressure is a prime contributing factor, the dispersion of the fuel is influenced, in part, by atomization and penetration of the fuel. (Penetration is the distance through which the fuel particles are carried by the kinetic energy imparted to them as they leave the injector or nozzle. Friction between the fuel and the air in the combustion space absorbs this energy.)

If the atomization process reduces the size of the fuel particles too much, they will lack penetration. Lack of sufficient penetration results in ignition of the small particles of fuel before they have been properly distributed or dispersed in the combustion space. Since penetration and atomization tend to oppose each other, a degree of compromise in each is necessary in the design of fuel injection equipment, particularly if uniform distribution of fuel within the combustion chamber is to be obtained. The pressure required for efficient injection and, in turn, proper dispersion is dependent on the compression pressure in the cylinder, the size of the opening through which the fuel enters the combustion space, the shape of the combustion space, and the amount of turbulence created in the combustion space.