Subsection 4.1.2 Current

Current refers to the flow of electric charge in an electrical circuit. It is the rate at which electric charges, typically electrons, move through a conductor. Electrons, which are negatively charged particles, are the primary carriers of electric charge in most conductive materials.

Current can be initiated and sustained in a number of ways, including

-

Chemical reaction.Batteries and fuel cells use this principle.

-

Electromagnetic induction.whereby mechanical power supplied by a prime mover is converted to electrical power by means of a changing magnetic field This is the principle used by electrical generators.

-

Photovoltaic effect.When sunlight strikes the surface of a solar cell, photons are absorbed by the semiconductor material used in the cell which causes some electrons break free from their normal positions, creating a charge imbalance.

-

Seebeck effect.The Seebeck effect is a phenomenon where a small current is produced between two different types of metals or semiconductor materials when a temperature difference exists between them. Thermocouples use this principle to produce electric signals for temperature measurement.

Current is measured in amperes (A) and is represented by the symbol I. It can be thought of as the quantity of charge passing through a point in a circuit per unit of time, or alternately as the rate of charge flow.

The ampere, or amp (unit symbol: A) is the unit of electrical current. One ampere is equal to one coulomb of charge moving past a point in one second.

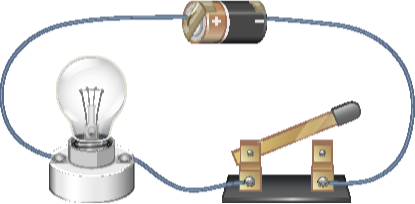

Consider the battery shown in Figure 4.1.3. The chemical reaction inside the battery causes electrons to move from the positive terminal to the negative terminal, making the negative terminal more negative and the positive terminal more positive. This creates a potential difference, or voltage across the battery terminals.

When the switch is closed, excess electrons will naturally be attracted to the positive terminal and they will migrate through the wire to attempt to equalize the charge. This create a flow of electrons that will continue until the chemical reaction is depleted and the battery “dies”.

Whenever a potential difference exists between two points in a circuit, whether created by a battery, a generator, or some other voltage source, it will drive electrons from the more negative point towards the more positive point. This is called electron flow, or electron current.

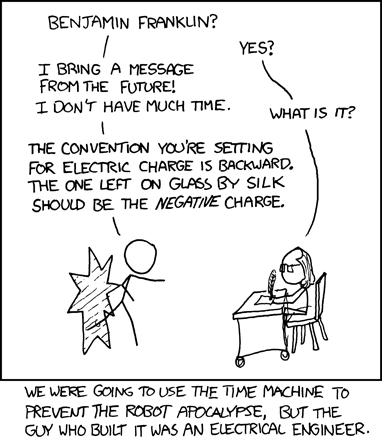

Sadly, electron current is not technically current! Current is defined as a stream of charge that flows from a more positively charged area to a more negatively charged area. This definition was adopted because we want to think of current as a flow going from a higher level (more positive) to a lower level (less positive), like water flowing down hill. Unfortunately, in 1752, before the nature of electric charge and electrons was fully understood, Benjamin Franklin unknowingly defined the charge on an electron as negative, so the direction of conventional current is exactly opposite to electron flow.

This definition of current, sometimes called conventional current for clarity, is the one used by physicists, engineers, and in textbooks. You should think of current as positive charge flowing from a positive terminal to a negative terminal, even though, in reality, negatively charged electrons flow in the other direction.